Curtis and Nancy Booth, of Turlock, California

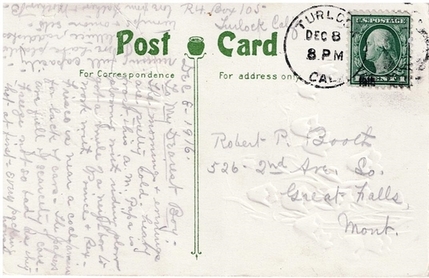

1916 postcard from Turlock, CA to Great Falls, MT

In December 1916, Mrs Curtis M (Nancy) Booth, of Turlock, California, sent a postcard to her son, Robert P Booth, at 526 2nd Ave South, Great Falls, Montana. It read ...

Dec 8 - 1916

To My Dearest Boy:

The mornings and evenings are pretty cold. heavy frost this a.m. Papa is plowing with riding plow [.] got a mule of a neighbor to work with Prince & Rex. Frisco is near a coal famine for lack of cars. The papers are full of scarcity of cars. Freeze not so bad as they thought at first. Every packing house nearing full capacity. We have planted lettuce, raddishes, turnips and onion sets.

love from Father and Mother B.

R4 Box 105

Turlock, Calif

Can we learn anything about these people and the times they lived in?

Robert Pearl Booth

Robert Pearl Booth was born December 12, 1889, in Corydon, Wayne County, Iowa, the first known child of Curtis and Nancy Booth. He was still living with his parents in Lindsay, Tulare County, California, on October 8, 1913, when he married Pearl Viola Hardesty. The couple must have soon moved to Montana where they were in December 1916 when Robert received the postcard. Their first child, Edith, was born in Bozeman, Montana, in 1918. By 1920 the family had returned to California and was living with Robert's maternal uncle Charles Thornburg in Orange County.

Robert and Pearl eventually settled in Kittitas County, Washington, where Robert worked as a postal worker. Their remaining three children were all born there. Robert died in Kittitas Co. on August 5, 1975, and is buried in the IOOF Cemetery in Ellensburg with his wife Pearl who died in 1994 and their son Robert who died as a child.

Curtis Monroe Booth

Robert's father, Curtis Monroe Booth, was born in March 1859 in Corydon, Iowa, the son of William and Hattie (Bishop) Booth. He married Nancy "Nannie" Isabell Thornburg on November 25, 1886, in Appanoose County, Iowa. She had been born July 2, 1863, in Red Oak, Montgomery County, Iowa, the daughter of Robert W Thornburg and Mary E Whitsell.

As mentioned, their son Robert was born in Iowa in 1889, but they soon moved to California, where their daughter Mary Garnet was born in December 1892. They had two other children: a child who died before 1900, and a son Oliver who died at the age of 6 in Long Beach, California.

Curtis was a farmer for his entire life in California, but did not seem to stay in one place for very long. Maybe "the grass was always greener" somewhere else. For a time line of his residences, click on the time line:

Curtis Booth Time Line

1886 25 Nov, Appanoose Co, IA married

1889: Corydon, Iowa, birth of son Robert

1892: California, birth of daughter Mary G

1896: Pasadena, voter reg

1899: California, birth of son Oliver

Jun 1900: Downey Township, LA Co, CA, census

1902: Fullerton, Orange Co, voter reg

1904/1905/6: not in Long Beach dir

Dec 1905 corner of Perris and State, Long Beach (Oliver's death notice)

1907: 1422 Elm, Long Beach

1908: west side of Oak Ave, Long Beach, 1st house n of Hill

1909 not listed in Long Beach

no dir for Lindsay or Tulare until 1957

1912: Lindsay, Tulare County, voter reg

1914: Lindsay, Tulare County, voter reg

Nov 1916: Turlock, voter reg

Dec 1916: RR 4, Box 105, Turlock - postcard

1917: RR 4, box 197, Turlock

1918: RR 1, box 382, Turlock

1919: RR 1, box 36, Turlock

Jan 1920: Whittier, wage worker, farmer

1924: Garden Valley, El Dorado Co

1926: Placerville, El Dorado Co

1928: Smith Flat, El Dorado Co

Apr 1930: Placerville, retired

May 1939: Anaheim, death

Curtis Monroe Booth died May 30, 1939, in Anaheim. His wife Nannie died September 23, 1944, in Orange County. They are both buried in Santa Ana Cemetery, Santa Ana. There is a picture of Curtis on his page on findagrave.com.

Supply Chain Problems—1916 Style

The part of the message on the card that got my attention were Nannie Booth's words "Frisco is near a coal famine for lack of cars. The papers are full of scarcity of cars. ... Every packing house nearing full capacity."

My first–and second and third–thought was 'I didn't think there were that many cars by 1916 for there to be a scarcity of them.' But after a few readings, I realized that Nannie was talking about railroad cars, not automobiles. So I started typing phrases into search engines and found out that, Yes, there was a shortage of railroad cars in 1916.

The Farmers and the Trains

To appreciate the California farmers' dependence on the railroad, take a look at this 1915 or 1916 picture from Hughson, California, near the Booths' farm in Turlock:

Shipping melons from Hughson, CA in 1915 or 1916

As the accompanying text, at the Calisphere, University of California site said:

In front of the Ward Lumber Company is a train locomotive with two freight cars visible ... [and] wagons full of watermelons that are powered by horses and mules. It appears that all are waiting until the watermelons can be loaded onto the freight cars. The railroads were the primary method farmers had to ship their crops long distances to large market areas, such as San Francisco, especially for perishable crops like watermelons.

Next realize that in February 1915 there was a surplus of 279,000 railroad cars, but by March 1, 1917, there was a shortage of almost 125,000 cars. The problem seems to have started in mid-August of 1916. (See Business Digest, January to March 1917, Vol 1, page 359, found at Google books.)

The number of cars didn't seem to be the only problem. Edwin E. Albertson, the marker reporter for the San Francisco Call, in an article dated November 22, 1916, quoting the Railway Age Gazette, says:

"If the railways now had enough cars to supply one for every one ordered, it is probable that when they got them all loaded their tracks would be so blocked that they would be unable to move much more traffic than they are at present handling. The term 'car shortage' is now, as always, merely a misnomer used to describe a condition resulting from the inablility of the roads to supply facilities enough of any kind to handle the business available."

The effect on West Coast farmers was "most severe" according to an article in the Los Angeles Herald, October 20, 1916:

Information gathered by the interstate commerce commission confirmed reports that the Pacific coast states are suffering most severely from the shortage of cars. It was also learned that Nebraska's grain crop and Colorado's mining products are in great danger of damage and incurring storage losses through lack of carriers.

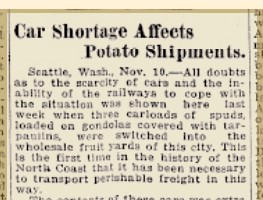

And the Chicago Packer of November 11, 1916, carried a story with the dateline "Seattle, Wash., Nov 10" and the headline "Car Shortage Affects Potato Shipments" which read in part:

Chicago Packer of November 11, 1916

All doubts as to the scarcity of cars and the inablility of the railways to cope with the situation was shown here last week when three carloads of spuds, loaded on gondolas covered with tarpaulins, were switched into the wholesale fruit yards of this city. This is the first time in the history of the North Coast that it has been necessary to transport perishable freight in this way.

The Coal Famine

The other problem that Nannie Booth mentioned was that "Frisco is near a coal famine for lack of cars." Other cities faced the same problem. Mr Albertson's article in the San Francisco Call said this:

... many Pennsylvania and West Virginia mines have been operating on half time, as they could not get cars to move their product.

The city of Columbus, O., confronted by a coal famine, has established a municipal coal and wood yard, in order to assure fuel to its inhabitants this winter, and Cleveland now threatens to do likewise.

The Report of the Department of Mines of Pennsylvania for 1916 said on page 5:

The operations of the year were of an unusual character. ... with sharp contrasts in prices and exasperating uncertainty, due to car shortage, labor troubles, and embargoes placed upon traffic."The Report of the Department of Mines" (Harrisburg, Penna, J.L.L. Kuhn, Printer to the Commonwealth, 1917), page 5.

Here are a few headlines about the coal famine from around the United States.

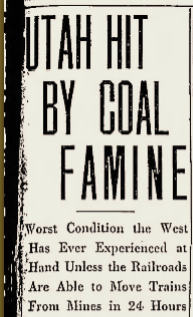

From Utah:

Salt Lake City, Utah, Republican, December 28, 1916, page 1

and Cleveland:

Akron Beacon Journal, October 27, 1916, page 1

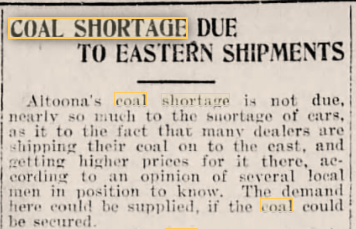

Even Altoona, in coal country, felt the effects:

Altoona, Pennsylvania, Times, page 10

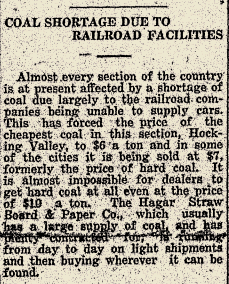

The October 27, 1916 edition of the Cedarville, Ohio, Herald, page 1, summed up the nationwide situation nicely:

Cedarville Herald, October 27, 1916, page 1

saying in part:

Coal Shortage Due to Railroad Facilities

Almost every section of the country is at present affected by a shortage of coal due largely to the railroad companies being unable to supply cars.

Causes

Why was there a rail car shortage? Why were farmers having a hard time getting their produce to markets? Simply put, there was a war going on. The Booths on their small farm in Turlock, California, were being affected by the war in Europe thousands of miles away.

Munitions and war supplies

The United States did not yet enter the war until 1917,

But soon after war broke out in August 1914, America began to supply food, materials and even munitions to Britain and other German enemies, such as Italy."Logistics and American Entry into the Great War" at the Defense Logistics Agency website.

Cleveland and Pittsburgh are dear to my heart, so here is what was going on in those two cities:

For Cleveland:

The years of U.S. neutrality were bonanza ones for Cleveland's industries, as its workers satisfied contracts for uniforms, weapons, automobiles and trucks, and chemicals for explosives. By the fall of 1918, it was estimated that the city had produced $750 million worth of munitions in the 4 years since the war had begun.""World War I" at the Case-Western Reserve Encyclopedia of Cleveland History website.

and for Pittsburgh:

1914 had seen a slump in American steelmaking, with output well below capacity. By mid-1915, all mills in the Pittsburgh area were operating day and night, even though the United States had not yet entered the war. Production throughout 1915 was at about 85 percent of capacity, reaching 100 percent during the fourth quarter. From 1916 onward, US Steel alone delivered more steel each year than all the plants of the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires combined. By the second half of 1917, some 75 percent of iron and steel output was supplying war demands."Facts About Pennsylvania in the First World War" at the World War I Centennial website.

The increased production of the factories meant they needed more coal. The coal had to be transported in. The manufactured goods and munitions had to be transported out. All of this required railroad cars.

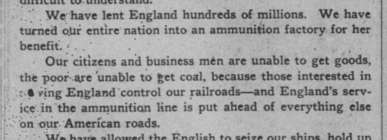

An editorial on the same page of the San Francisco Call as Mr Albertson's article, November 22, 1916, summed up the country's situation this way:

San Francisco Call editorial, November 22, 1916

We have lent England hundreds of millions. We have turned our entire nation into an ammunition factory for her benefit.

Our citizens and business men are unable to get goods, the poor are unable to get coal, because those interested in saving England control our railroads—and England's service in the ammunition line is put ahead of everything else on our American roads.

Shipping rates

Another consequence of the war was an increase in shipping rates. The San Francisco Call article by E. E. Albertson said that the rates for shipping iron ore on the Great Lakes had risen to a point where it was more profitable for ore boats to return home empty than to carry back coal, as they had done previously. This left the burden of taking coal to places like Minnesota up to the railroads.

I looked for some original sources online to back this up but didn't find anything, but it makes sense to me. The munitions factories would require iron ore and could probably pay what it took to get it.

Pacific shipping rates had increased also, which affected California farmers directly. Mr. Albertson's article pointed out that the rates on shipping routes from the West Coast to Asia had risen since the beginning of the war. This motivated at least one shipping company, the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company, to move their vessels from the west coast-east coast route elsewhere.

Tables 1 and 2 in "The War and Trans-Pacific Shipping," by Abraham Berglund bear this out. When the war broke out, Germany pulled its entire commercial fleet from the Pacific. Net tonnage carried under the British flag was cut in half from 1914 to 1916. Japan made up some of the difference but the overall net tonnage in July 1914, 237,004 tons, dropped to 147,744 tons in May 1916."The War and Trans-Pacific Shipping" in The American Economic Review, September 1917, Volume 7, Number 3, pages 553-568. Published by the American Economic Assocation.

Tables 3 and 4 show the change in freight rates from Asia to America and America to Asia. Increases were across the board, many more than 100%.

American-Hawaiian's decision might be referred to here:

"By the time the Canal reopened on 15 April 1916, American-Hawaiian had entirely suspended its intercoastal service, and its ships were operating only on war charters.""The American-Hawaiian Steamship Company, 1899-1919" by Thomas C Cochran and Ray Ginger, in Business History Review, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1954), pp. 343-365, published by The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Conclusion

When elephants fight,

it is the grass that suffers.

With all this going on, the California farmers were in a bind. Were the Booths able to sell their "lettuce, raddishes, turnips and onion sets"? Did they lose their farm? Their rural route address changed from 1917 to 1918, but I can't tell whether they moved or the route system was re-organized. If they moved, did they buy another farm in Turlock? Again, I don't know. There are probably property records out there somewhere that would answer those questions. But I do know that by January 1920, Curtis had left off farming for himself and was a wage worker in a walnut grove in or near Whittier, California, more than 300 miles south. I don't think that is what he pictured for himself when he moved to California in the 1890s.

Credits

The genealogical information for the Booth family came from the usual suspects—ancestry.com and familysearch.org—with a few vital records from the Washington State Archives thrown in for good measure.

The image of the farmers in Hughson, California, is in the Stanislaus Region History and Culture Image Collection of California State University, Stanislaus, Calisphere, University of California.

Business Digest, 1917, was at Google Books.

I found the Los Angeles and San Francisco articles at the University of California, Riverside, Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research's California Newspaper Project site.

The Chicago Packer article was in the University of Illinois' Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections.

The clippings from the Salt Lake City Republican, the Akron Beacon-Journal, and the Altoona Times were found on newspapers.com.

The Cedarville Herald article can be found on Digital Commons.

The drawing of two elephants fighting was available at pinterest which said it was royalty free.